The following was originally done as a presentation for Art Spiegelman’s seminar, “Comix: Marching Into the Canon” at Columbia University in 2007. I think it suited Art’s humor to assign me to do the required audio-visual presentation on a cartoonist we both perceived as far from my usual range of interest. He certainly did me a service in that while I also grew up with Peanuts, the process of making my power point slideshow and commentary added greatly to my appreciation of Charles Schulz’s comics artistry. Click on the images to enlarge.

___________________________________

“Style…should be in a continuing state of some evolution, while at the same time, it embodies a handy set of tools, a vocabulary for dealing with the experience one is describing, or for defining, often obliquely, the special nature of one’s own presence in the midst of this experience.…” -Donald Phelps

___________________________________

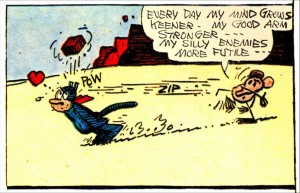

An important influence on Charles Schulz was George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, the early zenith of comic art: simplified, expressive ink line drawings in concert with each other and with thoughtful language.

___________________________________

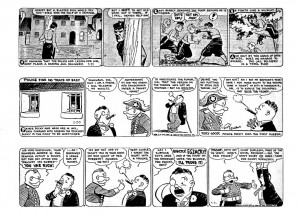

Schulz’s favorite cartoonist was Roy Crane, whose storytelling in Wash Tubbs mixes aspects of cartooning and realism. Crane’s work has a lot of clear white space, a feeling of air around the characters on the pages.

___________________________________

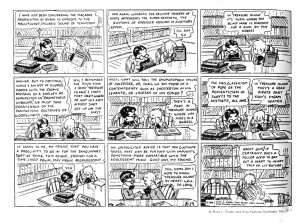

Another key influence, Skippy by Percy Crosby: the class consciousness of children who are vastly separated in terms of education, and a breezy pen and ink style.

___________________________________

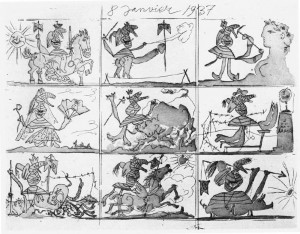

An actual comic strip by Pablo Picasso, another of Schulz’s favorites. I like how the main bandaged figure is kept somewhat on-model.

___________________________________

“Waiter! There’s a hare in my soup!”

Schulz wanted to be a New Yorker cartoonist, but didn’t have the nerve to submit his samples, like this one. One of his accomplishments was to successfully fuse the pared-down, elegant drawing and sophisticated irony of the New Yorker cartoon style to comic strips.

___________________________________

A charming drawing from L’il Folks, his precursor strip to Peanuts.

___________________________________

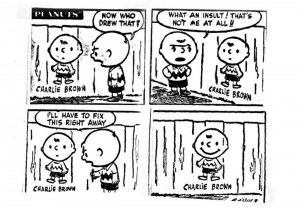

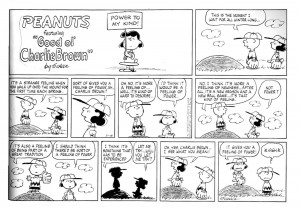

Peanuts debuted in 1950. Schulz immediately began pushing the envelope with his characters. Charlie Brown’s isolation and depression is omnipresent. In this very early strip he has a virtually hysterical reaction to being ostracized. Much humor is based on pain, and Schulz’s children were often all about pain.

___________________________________

This shows Charlie Brown’s self-image: as a happy kid. This was not borne out by the next 50 years of daily strips.

___________________________________

Charlie Brown became instantly recognizable. Contemporary popularity does not ensure one’s place in history, but in addition to creating indelible characters that resonate deeply in the American consciousness, Schulz was able to use his form to express complex sociological and psychological observations.

___________________________________

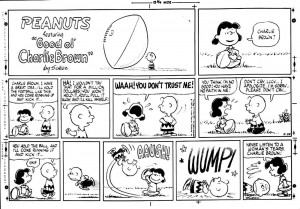

It is often quite a dark picture of life that Schulz give us. In this case Charlie Brown is not paying attention, which the calculating Lucy takes advantage of, along with his chivalry. But what he is saying is that he is neglecting more important matters to go to a bad movie, just to get something for free. Perhaps Lucy does him a favor, he is overreacting and should go home to his homework. As well, if his chivalry was real, he would have been happy to give up his place to his female friend.

___________________________________

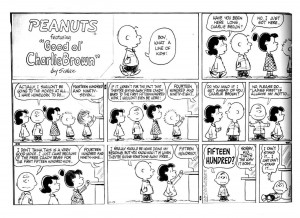

Optimism is unfounded. The manipulative Lucy tells Charlie all women can’t be trusted, specifically their “tears.” The behaviors of Lucy and the other female characters could take their own separate analysis, Schulz still has issues from childhood that he lays out.

___________________________________

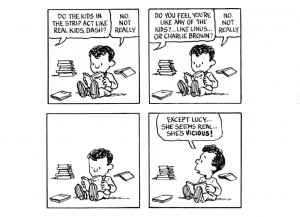

Schulz didn’t like Lucy’s character but she suited his storytelling purposes so well that she became essential. All of his characters have issues themselves, and with each other. Themes of abusive relationships and unrequited love are all over Peanuts. This panel refers back to Krazy and Ignatz.

___________________________________

Here Lucy relentlessly corrupts Charlie Brown’s long-awaited moment of pleasure, the first day of baseball season. Schulz decried the decline of American sportsmanship. He refined his concepts and evolved his drawing for clarity and simplicity of expression; ideal as a vehicle for his ideas, and ideal for efficiently producing a daily strip.

___________________________________

Schulz said he thought Charlie Brown deserved some of the abuse he got because he was arrogant. In Marxian terms he is in false consciousness, fixed in a cycle of failure and disconnection. He can never achieve any status. His creator, though, retained the means of production. Schulz controlled his creation and did his own work with no assistants.

___________________________________

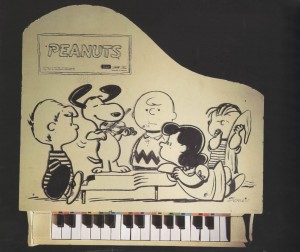

Even the product drawings extend his themes. In this group Schroeder is a prodigy being seduced by the tormentor Lucy. Linus, when he’s not oblivious as he is here, is capable of acts of extraordinary dexterity. Snoopy plays violin, speaks French, and has Van Gogh and Andrew Wyeth paintings in his doghouse. Look at the expression on Charlie Brown’s face. Is it incomprehension? Jealousy? Embarrassment? What can Charlie Brown do? Charlie Brown is in the center, but feels marginalized. He looks at us, or at the void.

___________________________________

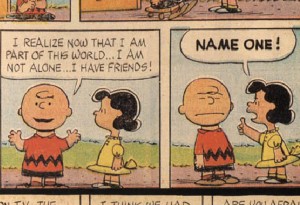

This reminds me of the beginning of Maus, where little Art is deserted by his buddies and runs to his dad, crying. Vladek says, “Your friends? Lock them together in a room with no food for a week…then you could see what it is, friends.”

___________________________________

Art Spiegelman’s perfectly timed version.

___________________________________

“It’s kind of a parody of the cruelty that exists among children. Because they are struggling to survive.” -Charles Schulz

___________________________________

“These children affect us because in a certain sense they are monsters…because we realize that if they are monsters it is because we, the adults, have made them so.” -Umberto Eco

___________________________________

Al Capp said: “The Peanuts characters…wound each other with the greatest enthusiasm. Anyone who sees theology in them is a devil-worshiper.”

___________________________________

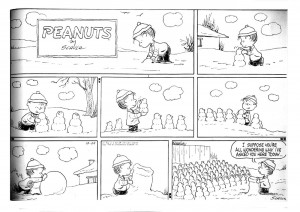

Linus is not a monster, he’s Lucy’s little brother, and we see him here building himself someone that will listen to him. Is it an Army, is that a cannon? No, a congregation and pulpit. Linus has evangelical Lutheran leanings. This reminds me of Roy Crane, it’s a beautiful strip.

___________________________________

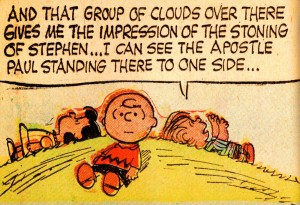

Linus humbles Charlie Brown with his visionary imagination. Linus frequently quotes the New Testament in context.

___________________________________

A philosophical debate on the mound, tiny children grappling with crucial issues, Linus contextualizing. This picture has formal and abstract compositional qualities, balanced in harmony (like “The Feast in the House of Levi” or “The Last Supper”).

___________________________________

Schulz’s output was as often more humorous or lyrical strips, but I have chosen to focus on his more serious aspects, because that terrible irony expressed through masterful use of his medium is what elevates his work to Art.

___________________________________

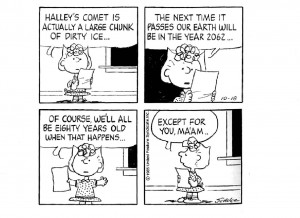

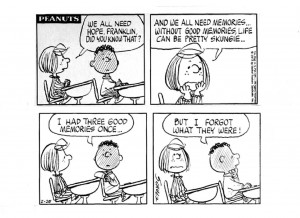

Schulz introduced an African American character in 1968, Franklin, whose father was in Vietnam. Franklin has no memories, which embodies the critiques of colonialism and speaks of the quandary of the descendants of African chattel slaves, cut off from their history. I may be reading into it with hindsight, but Schulz was by all accounts a voracious reader.

___________________________________

Is the Artist influenced by society, or does Art influence society? In Schulz’s case both apply. Schulz explored major issues in his strip, which becomes impressive when you realize that such feelings were delivered to 360 million readers.

___________________________________

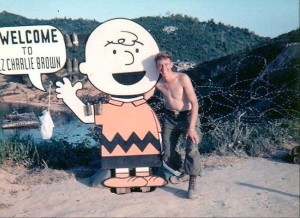

This is Landing Zone Charlie Brown in Vietnam, 1968. I can’t imagine how Schulz felt if he saw this.

___________________________________

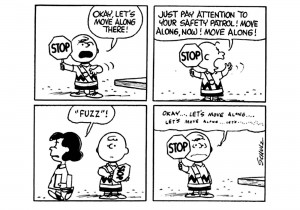

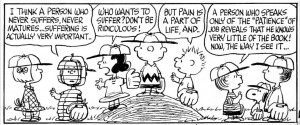

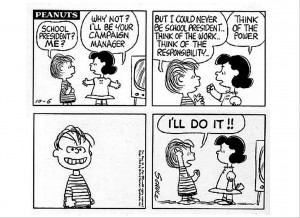

In this hard world, even gentle Linus is momentarily seduced by Lucy’s cynical litany. Even though conceptually adult, Peanuts was on the comics page. Children like me who grew up with this strip were being informed by Schulz’s observations.

___________________________________

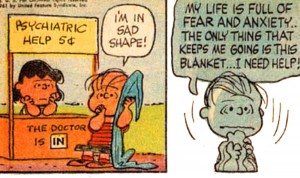

With horrible logic Schulz made truth-teller Lucy a psychiatric therapist. And, sometimes faith is not enough for Linus, who is often overcome by high anxiety. His security blanket has been entered into the psychiatric lexicon. The level of fear of these children, their apprehensions in dealing with a world that seems forever out of their control is what has always stuck with me when I thought of Schulz’s work.

___________________________________

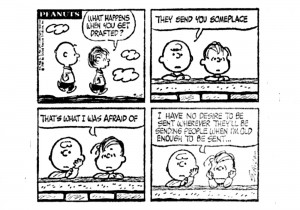

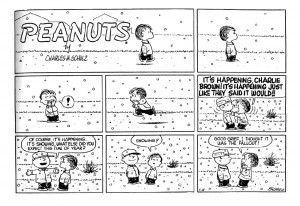

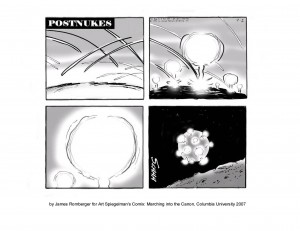

I remember this one well from when I saw it as a child, it was a clear expression of it’s time. This gets right to the “nut” of it, for me. It tormented me for a while in preparing this presentation. What is it about these characters, their shape? It was right there on the edge of my brain, something almost subliminal. I then had a little Peanuts epiphany.

Schulz was drafted in 1943, spent two years training, and then served in Germany as the war wound down. At one point his platoon camped in a swamp near Dachau. He said that what he remembered most about the war was loneliness. But suddenly…

…”everything changed.” I think this monstrous act to end a monstrous war imprinted on Schulz. The form of Charlie Brown, all tied up with fear and guilt, aligns with the alien image. He is the inheritor of the world we have built. Charlie Brown is the bomb.

___________________________________

___________________________________

First published on The Hooded Utilitarian