Since I am precisely the type of brutally obsessive yet overly sensitive observer that qualifies me to write for The Hooded Utilitarian, I am unable to ignore a few references I have seen online to my “fannish adoration” of the work of genius cartoonist Alex Toth. Answering them also gives me the opportunity to address some critical shortfalls that I have seen in the literature about Toth.

I do feel that Toth’s work is head and shoulders above that of most artists who have worked in the medium thus far. I and many other artists find Toth to be a great teacher. It is instructive to figure out how and why his odd approach works so well. Artists may not see his art in the same way as someone who is not an artist, but there are also many, many non-artists who appreciate the depth of Toth’s skills—and some who do not.

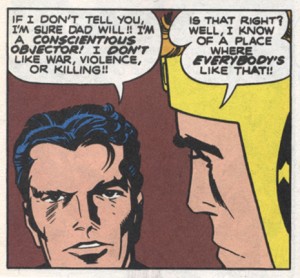

A critique that is often leveled at Toth should be dispensed with. Unfortunately, in order to appreciate his work, one must overlook the quality of the writing in most of the stories he drew. That can be said for every four-color comic book artist that worked with writers. But some seem to blame the artist for this. Even though Toth had higher artistic standards than his contemporaries, he was not any more responsible than they were for the texts they worked with. If not for bad scripts, there would be no Toth comic book art and in fact, there would be no comics at all.

A problem may be that deprived of worthy words to analyze, text-oriented critics are unsure how to approach work that is so dependent on the art. Toth improved the stories when he could, but as I detailed in Toth vs. Kubert, such upgrades were often unappreciated by his employers. The problem can be laid at the feet of the publishers, editors and writers who are responsible for the stories. That said, Toth took such stories as he was given and was able to transform some of them into Art.

But perhaps my critics have a point. I must ask myself, why am I so obsessed with a few old-school artists like Toth and Jack Kirby that I waited until relatively recently to notice all the work that has been done since the 1970s? Why did I take decades to read the work of Jaime Hernandez and other brilliant, inventive artists who have moved the comics medium forward? Why would I for so many years continue to examine the same small pile of treasured, decomposing comic books, as if I could continually find inspiration in their chipped newprint pages?

I have to conceed that my appreciation for Toth in particular was sparked by a personal catalyst, although I didn’t truly make the connection until a few years ago when I read Daniel Clowes’ pamphlet Modern Cartoonist. A passage written with some satirical intent still cut deep:

“Imagine…a child born into a hellish marriage, the details of which are so horrific that they are never discussed. His parents soon divorce and an older brother, the only witness to the horror-years, is too traumatized to communicate to the younger child. The only transmission of information comes indirectly from the older brother’s stack of comics, remnants of the hellish marriage years, that express, through his selection in buying these particular comics, the nature of the trauma in mythic/symbolic terms (hags, mad scientists and invulnerable super-tots). In a house that has repressed emotional horror to a lifeless approximation of “normalcy” these comics are a record of unspoken and unspeakable truth. If the young boy should one day create his own works of art we could expect him to in some way address this hidden language and to interpret his notions of the truth based on this experience.”

Clowes partially explains my fixation. Everyone’s “Golden Age” falls around the time that they are 12 or 13 years old, while they are forming their view of the world. I grew up with my big brother Michael, who was older than me by three years. We were very close through the many moves my family made, from Long Island to a succession of small towns in upstate New York, and through the births of our sister and younger brother. I looked up to him and he watched out for me.

As our family grew and we got older, Mike began to withdraw from me. Perhaps it was just a natural big brother thing; three years is a significant span at that age and I could be a pain, I’m sure. But Mike had problems. He had conflicts with bullies at school and one way or another always seemed to take his lumps. He began to get migraine headaches, then he had some seizures that resembled those of epilepsy, most dramatically in school and once while the whole family was sitting down to dinner. He underwent a barrage of medical tests to see what was wrong. He had a tangle of veins in his head and so he had an operation. I had to submit to many of the same tests as Mike to determine that I did not have the same problem, which was frightening of itself. So I had some idea what was happening, but I still did not grasp its enormity.

Mike recovered from brain surgery and faced the fragility of his existence. I remember being afraid to think of what was happening to him, of not wanting to acknowledge anything was wrong. He began to hang with the hippie kids and smoke cigarettes. He was photographed for the high school yearbook with his hair hanging in his eyes and as we used to say, “flipping the bird.” He closed himself in his room and listened to loud rock and roll. I also mostly stayed in my room with my drawing, my comics and books. I liked Kirby’s stuff but at that point I was perfectly happy to read Hot Stuff, Betty & Veronica or those big 80-Page Giant annuals with Rainbow Batman, Batdog and Batmite—I wasn’t yet so particular. Mike liked only war comics. He had a big stack of the Joe Kubert-edited DC war books.

And here it is: after reading Clowes’ pamphlet, I recalled a time when I was around 12 or 13. I wanted to hang around with Mike—it was hard to nail him down, because when he was feeling well enough, he wanted to get on with being a teenager. So, in an attempt to engage his interest I went to his door and knocked. When he opened it, I asked him, “Who do you think is the best comic artist?” Without hesitation he said, “Alex Toth.”

This ploy gained me at least a brief entree into his den. What Mike showed me to prove his point was Soldier’s Grave, a short, tragic backup story written by Robert Kanigher and drawn by Toth. It presents a mortal hand-to-hand combat between two men on the periphery of a massive battle in ancient Egypt. I recognised the style of the art, I had seen it before in a Zorro comic that I had glimpsed and coveted while waiting at a dentist’s office. Mike told me, “There’s no question, this guy draws the best, it’s the most real….you can really feel the story the way he does it.”

I valued Mike’s opinion and that he took the time to share his expertise. I would not get many more intimate moments with him. He would go on in the next two years to endure more seizures and more operations and hospitalizations, only to die of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 18. This tragedy touched every aspect of my family’s lives and I believe that we are all still greatly affected. Mike left me with his war comics, and so I face the root of my obsession.

This does not explain entirely my preoccupations, but it certainly predisposed me to find meanings in art that allow me to deal with the world I live in. I examined Mike’s comics at length and had to agree that although the other artists who rendered the bloodless DC wars made everyone look suitably grim and frazzled, Toth’s people breathed and felt pain. He took chances with how much the reader needed to see in order to understand what was going on. The images were oddly cropped, the characters often partly obscured, their motions caught at seemingly random angles. He gave the reader credit for intelligence. At the risk of repeating my previous post, Toth rarely if ever did better than his art for Kanigher’s White Devil, Yellow Devil.

In another artist’s hands it might have read like a typical Kanigher “no good deed goes unpunished” tale, but the way Toth drew it, it seems as if real people are on the page. A G.I. interrupts his duty of killing his enemy when he notices that the man he fights is even younger than himself. Despite this act of mercy, his enemy is forced to do him in, then is tortured by guilt until he buries his victim—and subsequently pays for that act of respect with his life. In other DC stories the soldiers look prematurely aged, lined and haggard, but Toth draws his to look young and vital; in this way he amplifies the tragedy of war, where the young must fight the battles begun by old men.

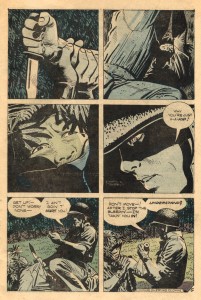

Much of the story is told with images alone. This must have been dictated by Kanigher’s script, but it is clear that Toth made many decisions that inform the narrative: in his “casting” of the characters and locations, in his rendering of motion perspective (his choice of viewing angles and composition) throughout and in his refinement of the pacing through page design and the subdivision of panels.

This page shows an effective transition from utmost tension all the way to calm. Panel one is very similar to a panel from Soldier’s Grave that was shown in my last Toth essay. The first three panels are about thrust and weight: the weight of the G.I’s stabbing arm being restrained, his body’s weight holding the other down, the weight of his hand pressing the other’s mouth to silence him. In panel four Toth highlights the soldier’s eye within the shadow of his helmet to show his dawning comprehension of the nature of his opponent. The tension is reversed and dispelled in panels five and six as the G.I. pulls his enemy up and binds his wound. Toth’s handling goes beyond serving the story, it unifies with the text while it affords the more significant amount of narrative information. Through the sensitivity of his drawing and composition Toth takes this simple tale and makes it resonate.

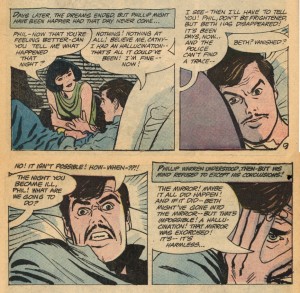

The Devil’s Doorway in House Of Mystery #182 has also long been a favorite. As a child I saw, in the drawings Toth did of the agonized father who unwittingly causes his daughter to be abducted by a demon, the face of my own dad who could do nothing to alleviate the pain of his eldest son. Even now Toth’s drawings affect me, in their gestures and expressions I feel with the characters.

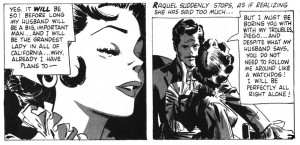

The Devil’s Doorway may be one of Jack Oleck’s better stories, or not. Joe Kubert thought that the Kanigher/Toth stories represented the writer’s best work. Toth’s stories aren’t all bad, but most often what is good about them is what he did with them. To an artist, Toth’s work is like a challenge. It implies potential—it says, “I took a clunker and turned it into a Rolls Royce…what could you do with something of substance?” Perhaps this is where his critics stall: his art can seem deceptive when the text is undeserving of the depth he implies, as in the Zorro stories that I finally read in Image’s collection.

However flimsy the excuse for a story, Toth made it speak as effectively as he could. That he was able to bring so much intensity to pulp entertainment is a testament to his commitment to the low-paid field of comic art. That can also be said for many artists in the short history of the medium. If weak stories make Toth unworthy of analysis, then the same goes for every artist who worked in comic books.

But there is yet something else that Toth brings, that can also be seen in the work of his nearest contemporary in terms of ability and dedication: Jack Kirby. Both men drew kid’s comics as if their lives depended on it. Both evolved strikingly individual styles of design and draftsmanship, both concerned themselves with the nuanced acting of their characters. Both took a comprehensive approach informed by observation and experience to their art, and through it expressed the turbulence and complexity of the human experience of their times.

Toth and Kirby were driven by trauma, Kirby by his desire to escape the poverty of the Lower East Side and his experiences in the bloody battlefields of France in World War II, Toth by something referred to obliquely by his oldest friends but yet-undocumented, a “problem in his family” growing up. Many involved in comics have similar, personal catalysts. Jim Steranko finds his motivation for making art in painful moments from his childhood. As does Art Spiegelman: Maus slays the reader when his father calls him by his dead brother’s name; likewise Art’s intro to the 2nd edition of Breakdowns hinges on the abuse of his mother at the hands of his bullying classmate. Besides their diverse technical accomplishments, what Kirby, Toth, Steranko and Spiegelman share with artists like Hernandez, Clowes, Tony Salmons, Chris Ware and more recent discoveries (for me) such as Frank Santoro and Sammy Harkham is the emotional investment which can be seen in their work.

In effect, Toth and Kirby became my surrogate parents. Their linear heroes got me through some rough times and imprinted on me. Their drawings diagrammed and made visible what I thought America was supposed to be about: common decency, good sportsmanship and living the dream of the great melting-pot of the world. They drew people that looked like my parents, who projected images of a tough but fair-minded folk who dealt with problems in a straightforward manner. My own bereaved parents never truly recovered their equlibrium after our loss, though, and much remained unspoken; their children inevitably felt the repercussions. I found my own solace. In comics entire universes can be found to escape to, to explore, as we all know.

If you’ve gotten this far you’ve noticed that this essay is more about me than Toth. As with Clowes’ postulate artist, the charged drawings of conflict by Toth and Kirby formed the hidden language that mapped my own trajectory. But if by dint of my late brother’s judgement Toth is my daddy, then Kirby is my mother! Kirby is the nurturing, empathetic creative force; Toth demands patriarchal control, he dominates impoverished texts by means of an reductive linearity. I’ll leave some of this for Sigmund to unravel. Outside of my more subjective biases, my take on these artists is not always based on hard fact, but on my cross-referencing of what is on the record along with what I am able to glean by looking at their work. I only know them by their work. While Kirby was very kind and supportive when I met him for a brief moment in 1983, I had no personal contact with Toth, although I tried. If he was like a father to me, he was a hard, absent one.

Before I ever read an interview with the artist to know of his opinionated eccentricities, the Kansan artist and teacher Dave Cook gave me Toth’s address. In 1999 I mailed him a copy of 7 Miles a Second. I thought that given the apparent sophistication of his work and all the time Toth spent in Hollywood, surely he would be able to handle a comic about a child prostitute who becomes a homeless teen and then as an adult dies of AIDS. My mistake. I did not get a reply to the letter I enclosed. Dave heard from Toth and then wrote to ask me what I had sent. Toth hadn’t appreciated it and had grumbled to Dave. Later when I read Toth’s columns, I thought I understood. The book had likely embodied for him everything he railed against in comics regarding subject matter. Despite his occasional, more ambitious statements, Toth drew comics for kids.

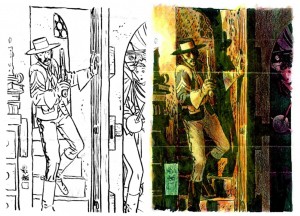

In 2002 Dave secured for me the artist’s permission to print a beautiful before-and-after Toth drawing in the zine Marguerite and I did for three issues, Comic Art Forum.

My caption said, “Toth did the above drawings very recently, and they provide a profound lesson in light and space, and design; hard-won insights from one of the all-time greats of comic book art.” I sent Toth some comp copies, with another note. Again, he didn’t write back. Our mutual friend wrote to ask him what he thought. Dave relayed to me that Toth was “impressed” with what I wrote in CAF. He had even mailed the extra copies that I had sent him “out to a few friends.”

He was impressed…that I praised him well.

——————————————

First published on The Hooded Utilitarian

Sources

Clowes, Daniel. Modern Cartoonist (pamphlet). Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 1997.

Kirby, Jack. “The Glory Boat.” Inks: Mike Royer. The New Gods #6. NY: DC Comics, 12/1971.

Toth, Alex. Zorro. CA: Image Comics, 1999.

Toth, Alex. “White Devil, Yellow Devil.” Script: Robert Kanigher. Star-Spangled War Stories #164, (K858), NY: DC Comics, 9/1972.

Toth, Alex. “Soldier’s Grave.” Script: Robert Kanigher. Our Fighting Forces #134 (K646), NY: DC Comics, 12/1971.

Toth, Alex. “The Devil’s Doorway.” Script: Jack Oleck. House of Mystery #182, NY: DC Comics, 10/1969.

Zorro painting courtesy of Dave Cook, copyright 2011 by the estate of Alex Toth. Zorro copyright 2011 by Disney.

——————————————

Previous articles in this series:

Cursing the Darkness: The Last Horrors of Alex Toth

——————————————