Jaime Hernandez uses the temporal flexibility of the comics medium to work like memory: moments that are far separated in time recontextualize when put in proximity to each other. He shows that the ways people treat each other resonate unpredictably through their lives. In the world he has built on paper and in ours, passion can be fleeting, violence can happen in the blink of an eye and both can have long-lasting repercussions.

Hernandez’s recent comics show psychological insight and a command of expression and gesture that transcends his earlier efforts. As he refines the economic grace of his storytelling, he delves into the formative years of his characters to motivate them.

Secrets hinted at over the years are overtly revealed in Browntown, which is cut with flashbacks to a time when the teenaged Maggie’s family moves from Hoppers to Cadeeza to be closer to where her father Nacho works, so he can spend more than just alternate weekends with them. But, Nacho’s infidelity is revealed by his behavior at a party attended by both his wife and his young employee/mistress Miss Varga, who makes a point to cruelly inform Maggie of the disparaging nickname of her new neighborhood. Nacho thinks he has uncovered a betrayal when a drunken former workmate of his wife says he visited her house while they lived apart; here perhaps he displaces his own guilt to her and so to their daughter.

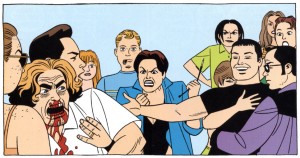

Maggie in her innocence percieves his half-serious disowning of her as only a joke and then does not understand her father’s violent reaction to her affectionate embrace. Now, on the one hand, he is freaking out because his wife and his girlfriend are both in that panel, a significance that Maggie and her mother are both unaware of. But also, possibly a baser sexual instinct provokes his panic; certainly Maggie could not imagine that he might be subject to arousal as a young girl climbs on his lap, even if she is his daughter. Perhaps, here is some of the rationale of misogynistic fundamentalism, men who repress women because of their own lack of self-control.

When Maggie later sees Nacho parked having an emotional scene with his lover, she places her as Miss Varga from the party and as the girl seen earlier leaving what she and his siblings had decided couldn’t be his car. The depth of her father’s betrayal destroys her trust, her idea of how the world is structured and when she then tells her mother what she saw, the family fully dissolves. Nacho won’t control himself and he isn’t protecting his family, which enables the ordeal that Maggie’s brother Calvin goes through and forces that little boy to take on the role of protector.

Left to his own devices and vulnerable, Calvin is initiated into a club of boys of varying ages that sit around in the grass with their pants down. Hernandez shows the boys mime heterosexual sex, though not engaging in actual sex. But, the older boy who leads this supposedly harmless homosocial group draws Calvin away from the rest to rape him repeatedly.

Hernandez shows the progression of abuse with understated taste in his increasingly appealing style, which makes it all the more horrific. The period shown is protracted, enough that both characters’ hair grows significantly longer. What is done to Calvin is long-term bullying and rape: he says “no” repeatedly, he expresses that it hurts again and again. The older kid threatens Calvin’s family several times when he tries to refuse to submit; his arm is twisted behind his back, he is forced. Ice pops are shoplifted and shared with Calvin as a show of exchange, which also makes him complicit in crime and solidifies the kid’s hold on him.

When the sociopath begins to spend time with Maggie, Calvin knows the boy’s practices and does not want him near his sister. He erupts and attacks the bigger kid for violating their pact: that if Calvin endures the abuse, his family will be safe. Calvin is badly beaten. When he gets home, there is a problem occurring involving Maggie that he doesn’t understand. Everything happens quickly; the family is breaking up, they are leaving town because of something unspoken, something bad that no one will tell such a young child. He mistakes the upset caused by Maggie’s exposure of her father’s cheating for something involving Maggie and his rapist. This is why Calvin does what he does, here and later in The Love Bunglers. His older, traumatized and disassociated self is still trying to protect Maggie.

A terrible irony of the revelations in these stories is that the reader knows much more than the characters do. As Calvin acts because he does not comprehend the true reason his family is falling apart, Maggie remains ignorant of what Calvin does out of love for her, she doesn’t realize who the older Calvin even is and eventually she denies her brother entirely.

__________________________________________

The first time I read The Love Bunglers, it unnerved me. A few days ago, I read it again and thought it was perfect. Still, I should restrain my interpretation until I see where Hernandez goes next, as I had to do with L&R NS #3, which is clarified by what transpires in the next issue. The scale of the lateral expanse he has developed makes it so he can continue to explore the spaces between and around what he has already established.

The most obviously outstanding aspect of Hernandez’s work is that his female characters are afforded, in their mesh of word and image, a depth of agency and complexity rivaled by no male cartoonist but Milton Caniff. It is hard not to single out Maggie for her particular charisma and I’m very impressed with Jaime’s most recent issue’s visual deglamorizing of such a beloved construct. His male characters are no less considered. Below, for example, Hernandez counterpoints Maggie’s subtle interaction with Ray by his frenzied coupling with “The Frogmouth,” a conflicted and sometimes tragic figure in her own right:

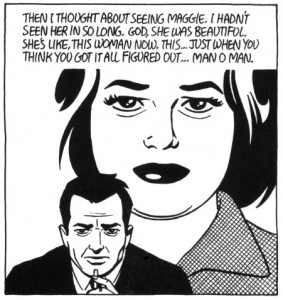

But it is Maggie who is imbedded in Ray’s consciousness; she’s unforgettable. Here’s one of my favorites of all of Jaime’s panels:

It reminds me a lot of one of my favorite Kirby panels since I was a kid, that I suspect Hernandez noticed as well:

Obviously such montages are well-worn romance comics devices, but Kirby was one of the initiators of the genre and Hernandez is one of his best students. In both stories these are significant moments in much larger, painstakingly set-up spreads of narrative; they are timed and emotionally keyed in the interaction of word and image so that the reader is driven to empathize with the characters’ yearning and to associate it with a similarly displaced attachment in their lives.

With Hernandez’s work, this identification goes well beyond sentimentality or nostalgia. I once sent him a letter that said, “Your work is great art because it is not only a pleasure to behold but also makes one consider one’s own experience with added perspective.” I can’t think of a better way to say that and it’s true, his work has given me many such moments of reflection. The director Jean Renoir wrote to François Truffaut, “It is very important for us men to know where we stand with women, and equally important for women to know where they stand with men. You help dissipate the fog that envelopes the essence of this question.” When I first read that quote, I thought of Jaime Hernandez.

________________________________________

First published on The Hooded Utilitarian

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.